An earlier version of the following was originally posted to Facebook: Oct 24, 2025.

My post on cursive writing struck a nerve. Good.

Romans invented cursive. There’s a reason colonial empires elevate it above other writing styles. There’s a reason people will think, “ooh fancy,” or “wow so neat!” when looking at English cursive writing (hereafter referred to as “cursive”)–classism. Racism. Ableism.

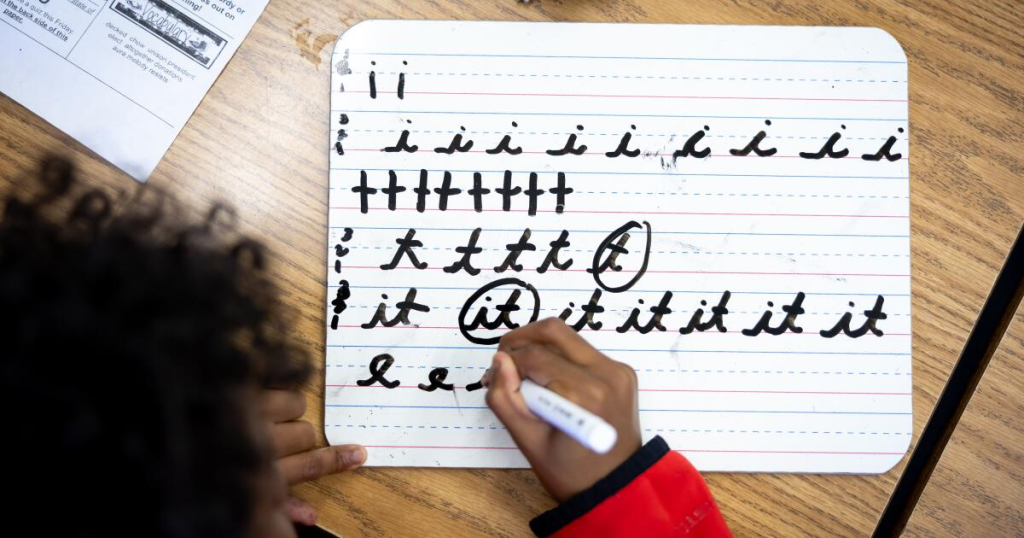

I am not arguing for the abolition of cursive, but of compulsory or mandatory cursive instruction. Rather than acknowledging the established benefits of differentiated instruction, proponents claim that teaching English cursive writing is one of the only ways to prevent future generations from becoming unpatriotic, illiterate Neanderthals.

I argue cursive writing is a useless skill that serves no practical purpose outside of a specialized industry like archival work, graphic design, etc. There is nothing inherently wrong with “useless” skills because “use” is subjective and skills dismissed as useless were often maligned for being feminine, low-class, or unproductive (i.e. anticapitalist).

Let me therefore clarify that I am speaking as an educator and my point is that compulsory cursive writing instruction for all students is a waste of class instruction time, energy, and labor. Offering the option in a History, 3-D Design, or Graphic Design class at the junior-to-high school level makes far more sense than compulsory instruction for all students in elementary classrooms.

There are many exercises and games toddlers and adults alike can practice or play to develop fine motor skills, hand-eye coordination, address dyslexia symptoms, or contribute to literacy development. Drawing exercises can increase a person’s spatial awareness and lead to the same results as forcing a child to write lines in script ad nauseam.

Parents and educators default to cursive because it’s a western cultural tradition, or as Lucio Bolletteri explains, “[c]hildren are taught cursive so they can use it in the classroom, and cursive is used in the classroom because children are taught to employ it. This is circular logic.” This fallacious cycle might be why proponents are often unable to address specific arguments and claim critics like me want cursive erased from existence.

I do not think any good faith arguments against compulsory cursive writing instruction in K-12 classrooms want cursive eradicated nor do they deny the growing body of scientific research on the proposed benefits of manual writing in classroom settings (See: Berninger, Ihara et al., Sawchuk, and Wiley & Rapp). That would be unscientific and unethical, yet cursive proponents refuse to abandon their straw man.

Besides anecdotal evidence, the most common counterarguments proponents of compulsory cursive instruction employ are that it leads to a slew of educational benefits. This makes anyone claiming cursive is a waste of time sound like anti-science conspiracy theorists when it is the pro-cursive camp’s support that stems from scientific illiteracy and misleading pop science media.

I can’t embed this John Oliver segment from Last Week Tonight due to age restrictions, but I highly recommend taking fifteen minutes of your time to learn about the ways mass media manipulates scientific research and published studies to sensationalize topics, sell products, or fearmonger.

Research does suggest that handwriting instruction contributes to information retention, long-term memory recall, and cognitive engagement, but the keyword is handwriting. Not cursive.

The majority of research into these subjects does not differentiate between handwritten styles, instead focusing on instrument.

Unfortunately, cursive proponents and legislators cherry-pick positive points from handwriting studies while simultaneously omitting potential drawbacks to cursive itself. Unless people look up the studies, they have no way of knowing whether someone is incorrectly specifying style or cherry-picking evidence.

It should be noted that most of these studies are inherently flawed because researchers started from a position assuming writing systems are a sign of civilization and intellect, using labels like “normal” or “typical” to describe students capable of holding instruments or engaging in graphical writing. Unless a disabled person is involved with the study, chances are the team’s biases regarding student capability, skill, or whatever metric being examined, will go unnoticed. The burden falls on disabled students, staff, and faculty to challenge those biases and expend our energy to educate colleagues and remind them we exist in “their” spaces.

Far too many academics operate within the core assumptions of neoliberal multiculturalist “equality” which functions as a means of institutional discrimination. Treating everyone the same despite their differences is part of a process called, “flattening.” Neoliberal egalitarian equality requires ignoring race, class, gender, disability, or any other intersectional experience embodied by students. The pro-cursive camp ignored ongoing criticism of this ableism in composition education research by erasing disabled people completely. They began from a cultural assumption, structure experiments for confirmation bias, and report results as empirical evidence.

Take the following for example:

“Our results clearly show that handwriting compared with nonmotor practice produces faster learning and greater generalization to untrained tasks than previously reported. Furthermore, only handwriting practice leads to learning of both motor and amodal symbolic letter representations.”

Wiley & Rapp, “The Effects of Handwriting Experience on Literacy Learning” (2021)

If a study claims students who practice handwriting and take physical notes in class are more successful in life, or their brains are “more developed,” but does not address how neurodiversity and disability were accounted for or whether they were even considered, what use is that research regarding a diverse student body? How might neurodiverse or disabled students be made to feel ostracized or inadequate due to their perceived inability to “master” a colonial skill, and how are handwriting biases impacting instructors?

When I was a kid in the 1990s, my 1st, 3rd, and 5th grade teachers believed boys naturally had messy handwriting and expected them to have “ugly cursive.” They were also overly-critical of girls who didn’t write “pretty enough.” My younger brother once came home in tears because he couldn’t quite get the hang of a few letters and the teacher called his writing “ugly.” He still writes in all-capital letters today because she, and another teacher, said it was the only way his assignments were readable.

After my dominant hand was paralyzed in 4th grade, I was never given another handwriting assignment and rather than adapting P.E. classes, I was sent each day to the library. In high school and college, teachers did not believe me or care that I was physically disabled because I refused to register through the university. This was the late 00s through the early 10s when schools did not have to do anything to accommodate students unless a legal document required.

I could write in cursive prior to my injury and I can write in cursive today, but during the recovery period I could not do anything with my hand or arm. I forced myself to do timed writing assignments during class despite the pain because I wanted to prove I didn’t need accommodating. So when I analyze these studies claiming students must be challenged in their work, asked to do uncomfortable tasks, or forced to write to demonstrate “skill mastery,” I do so from the perspective of a disabled kid erased from the data.

Challenging material or tasks might benefit some students, but pro-cursive studies often leave out research that found, “differing levels of disfluency… [like] illegible or hard-to-read stimuli might lead to a memory disadvantage, while more moderate disfluency would be the best for learning.” In the case of cursive, compulsory instruction for all students might mean some experience increased cognitive “processing costs, denoted by longer naming latencies, [that do] not confer a memory benefit” (Geller et al. 2021). Unsurprisingly, students respond differently to disfluency and stress concentration.

“[T]he issue is difficult to study because it’s hard to find children whose educational situation differs only in the style of handwriting. What’s more, a lot of the ‘evidence’ that does get quoted is rather old and of questionable quality, and some of the findings are contradictory. Simply put, our real understanding of how children respond to different writing styles is surprisingly patchy and woefully inadequate.”

While proponents might claim cursive writing benefits everyone and only makes writing more efficient, studies tend to show little difference in performance and information retention between the two handwriting styles compared to typing (Ball 2016; Barrientos 2016; Waterman 2014; Wiley & Rapp 2021). As Geller et al. summate, “When a finding fails to replicate, it is important to examine why. The fact that perceptual disfluency does not always promote positive learning outcomes raises the question as to whether disfluency is a desirable difficulty” (2021). The bulk of educational research suggests differentiated instruction accommodates various learning styles or preferences, disabilities, neurodivergence, and multilingualism and is the most effective approach for all levels of education.

Cursive, Colonialism, & Eugenics

The belief that compulsory cursive writing instruction is the best or only solution to neoconservative claims of social degeneracy or neoliberal claims of anti-intellectualism speaks to my initial point that compulsory cursive instruction is a colonial relic used to reinforce white supremacy.

Western European instruction was primarily religious no matter the institutional affiliation and reserved for men who were clergy, nobility, or from the wealthy mercantile classes. All students learned Latin or Ancient Greek, cursive writing, basic mathematics, and the Sciences (e.g. biology, psychology, philosophy).

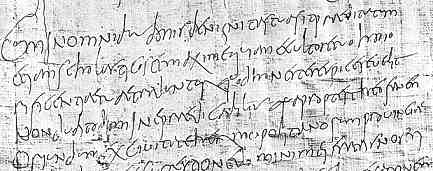

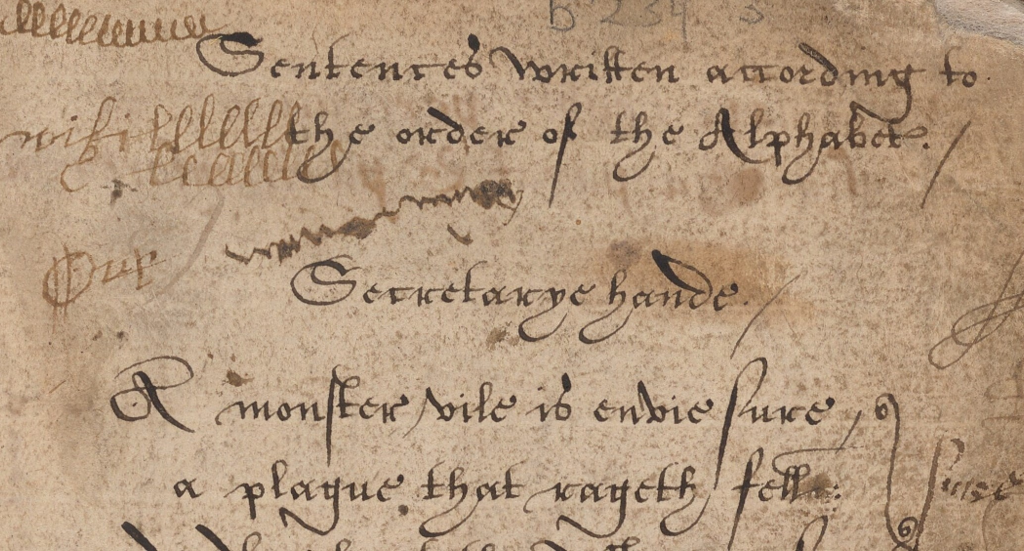

Evidence of cursive in English dates back to at least the 11th century, but “it wasn’t until the 17th and 18th centuries than cursive became standardized” (Gelb 2021).

Books and newspapers used block-style lettering since they were made with printing presses, but handwritten materials were produced in script or cursive. This meant people who could write prior to the 20th century most likely obtained formal education and their “cursive handwriting was considered a mark of good education and character” (Ball).

At the end of the 15th century, colonialism provided social and educational opportunities to some poor Europeans, or those in the global north, at the expense of those in Africa, Asia, and the “New World” because capitalists and land speculators needed ways to communicate and associate with their white subordinates without fear of prying eyes. However, stratified levels of education were introduced to manage exactly what those subordinates were permitted to learn.

Most people in western societies therefore remained unable to read contracts, study holy texts, or directly consume certain forms of art until the Gothic and Victoria eras (think penny dreadfuls or Charles Dickens’s serials). Literacy and the ability to write became a means of achieving social importance since communities had to rely on the state, their church, or hire a scribe to read aloud or draft documents.

Eugenicists ignored educational and social disparities, claiming pseudoscience like handwriting analysis was an objective measurement that could determine a person’s intellect and various aspects of their personality or subconscious. A person’s perceived inability to write “correctly” was thus a sign of social deviance or intellectual impairment resulting from “feeble-mindedness,” psychosis, or racial classification.

“Teaching of manuscript lettering (not joined up) only began in the United States in the 1920s, to some controversy. […] The U.S. and United Kingdom leave some discretion for when cursive is taught, but there is the assumption that it will become the pupil’s normal mode of writing. When cursive is taught, it may become compulsory, so children may be marked down if they don’t write this way. In France, the cursive form is virtually universal and highly standardized, and children are discouraged from developing their own handwriting style. Despite this diversity, the teaching of cursive is often accompanied by a strong sense of propriety. It’s simply the right thing to do.”

Philip Ball, “Cursive Handwriting & Other Education Myths” (2016)

All groups were subjected to eugenics testing in institutional settings like education, employment, and military service, but not all groups found themselves at a disadvantage. Jewish students, especially those of Ashkenazi descent, were integrated into U.S. public schools from community day schools in the late-19th century and they received concurrent instruction in Hebrew and English reading and writing which put them at an advantage compared to other students.

Ashkenazi Hebrew cursive diverged from square printing and Classic Sefardic hand in the Middle Ages “to write western European languages” and “exhibits French and German Gothic overtones of the so-called black-letter styles” (Britannica). Some English language cursive elements come from Ashkenazi Hebrew cursive like serifs and connected strokes, so Jewish students did not struggle at the same rates with handwriting assessments due to their historical exposure to English language cursive.

In the 1940s when US public schools began integrating women and the “dark whites” (Eastern Europeans & North Africans), then the Civil Rights movement won integration lawsuits through the 1950s and 1970s for Black and Indigenous children. White and Jewish families who did not flee to newly-built suburbs demanded public schools find a way to keep the “degenerates” and “savages” out.

Cursive writing instruction and “mental age” assessments, later re-branded “Intelligence Quotient,” were used to keep certain students in segregated schools, remedial courses, deny them scholarships, or refuse them jobs post-graduation. Until the invention of Braille, folks with visual impairments or the blind were considered less intelligent than the sighted and incapable of “higher forms” of communication and expression. Similarly, mute folks were given the medical diagnosis, “dumb” and considered intellectually stunted even if they could write.

These new standardized eugenics assessments functioned so effectively that disabled students were banned from U.S. institutions until the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975) passed, meaning schools remained functionally segregated through the 1980s.

Through the 2010s, pop news sites like BuzzFeed offered “quizzes” that asked questions about handwriting to analyze a person’s temperament, romantic prospects, and more. The average person does not know the eugenics origins and applications of these fun quizzes, so the belief that handwriting is somehow an indicator of personality or behavior persists. It should not be surprising that we are experiencing a resurgence in illiteracy and educational discrimination.

Cursive Instruction & Literacy

My initial Facebook post about this subject was inspired by the Oklahoma Senate proudly announcing they’re forcing cursive instruction on students again when they are near the bottom ranking for student literacy. There is no panacea for this “epidemic,” yet Anglo-European neoliberal education continues to promote standardized curriculum, multiple choice testing, harmful praxes, and 20th century eugenics.

National Center for Education Statistics (2024-5):

- 34% of adults lacking literacy proficiency were born outside the US.

- Massachusetts was the state with the highest rate of child literacy.

- New Mexico was the state with the lowest child literacy rate.

- New Hampshire was the state with the highest percentage of adults considered literate.

- The state with the lowest adult literacy rate was California.

National University Adult Literacy Statistics (2023-5):

- In 2023, 28% of U.S. adults scored at or below Level 1 literacy, indicating significant difficulty with everyday reading tasks.

- In 2023, 29% of U.S. adults scored at Level 2 literacy, showing basic reading proficiency but challenges with complex texts.

- In 2023, 44% of U.S. adults scored at Level 3 literacy or above, indicating strong reading and comprehension skills.

- About 130 million U.S. adults (54% of those aged 16–74) read below a sixth-grade level, according to modeled estimates.

- Approximately 45 million U.S. adults are functionally illiterate, reading below a fifth-grade level.

- 21% of U.S. adults are classified as functionally illiterate, unable to complete basic reading tasks.

- The average American reads at a 7th- to 8th-grade level.

- Adults scoring in the lowest literacy levels (Level 1 or below) increased by 9 percentage points between 2017 and 2023.

- U.S. adults’ average literacy scores declined by 12 points from 2017 to 2023, according to the latest PIAAC data.

- In 2023, 46% of U.S. adults had a literacy proficiency at or above Level 3.

According to “the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)’s 2022 global rankings for reading achievement of 15 year olds by country, the US was ninth. American students trailed behind Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) powerhouses such as Singapore, which was in the top spot, and Japan at number three.” Yet in 2022, 21 states required compulsory classroom instruction on cursive writing.

If cursive writing instruction was the only, or most surefire way, of increasing student literacy and cognitive abilities, then why are European colonial nations like the United States, Canada, France, and the U.K. consistently ranked behind east Asian and Scandinavian nations who do not impose mandatory instruction?

One could argue that students in nations like Japan or China receive instruction for their own script writing styles, but languages composed of Egyptian hieroglyphs or logograms are not comparable to English cursive allographs which are simply defined by connected or looped letters. An equivalent comparison would be English and Shorthand.

The English language is a lingua franca and shares global linguistic domination with Ashkenazi Hebrew, Arabic, and east Asian logographic scripts because legal or political figures used colonialism as the primary vehicle for language standardization. Indigenous spoken and written languages were replaced with Latin and Chinese; for example, scholars note that several modern forms of Japanese kana, Vietnamese nôm, and “South” Korean han’gŭl were based on Chinese, or “at least to their ideal square shape” (Kornicki). Ideal, huh?

So if writing instruction is a tool of colonialism, not an objective scientific measurement or cure for illiteracy, what ground does the argument for compulsory cursive writing instruction have to stand on?

I also question the reliance on perceived writing skill or handwriting characteristics as a measurement for literacy because “writing instruction has tended to focus on content-neutral tasks, rather than deepening students’ connections to the content they learn” (Sawchuk 2023). I ran into the content debate among composition instructors during my graduate studies and found myself at odds with professors and colleagues alike who saw contextualized thematic content as a distraction or instructors platforming personal beliefs.

Pretending classrooms are objective spaces and students are tabula rasa is another colonial relic and we have John Dewey to thank for its grip on U.S. education because he adapted not only the likes of Johns Locke and Galton, but Captain Pratt’s Indian boarding school model. This is why U.S. education is stratified at all levels and students at public institutions receive the minimum level of state-approved instruction required to enter the labor force.

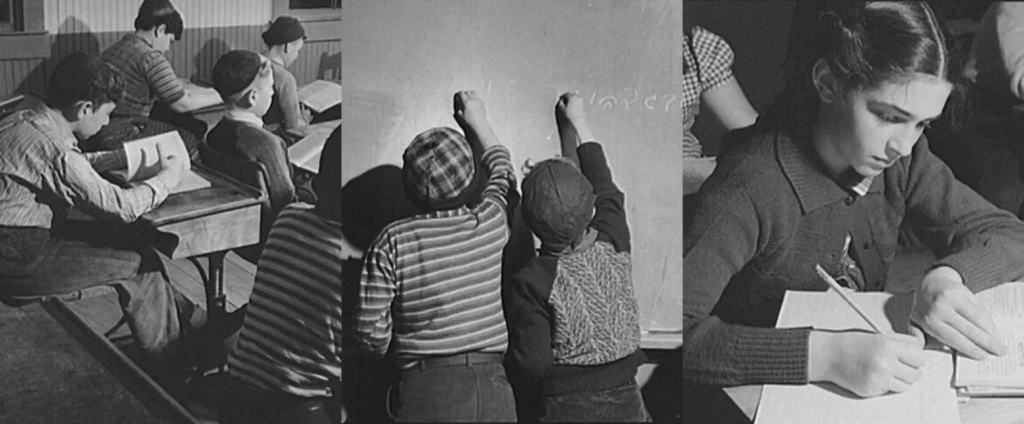

Photo: Library of Congress.

Literacy itself is not a neutral concept because it has always been tied to an individual’s social status and intersecting factors applied by external forces or actors (e.g. racism).

“The capacity to read and write, commonly known as literacy, stands out as a pivotal determinant in shaping an individual’s career trajectory. Individuals with literacy skills have access to a broad spectrum of career possibilities, including highly skilled and well-paying positions. Conversely, those lacking literacy face severely restricted options, with even entry-level, low-skilled jobs posing challenges to secure.“

Through the 20th century, white students in affluent neighborhoods read Plato, Shakespeare, Milton, and modern writers like George Orwell, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and Tennessee Williams. A progressive teacher might include women like Mary Shelley, Virginia Wolfe, or Zora Neale Hurston. Students would be taught how to read poetry, drama, fiction, philosophical, and scientific writing, and practice writing their own.

Meanwhile, students in working class (read: poor white), urban (read: Black) districts, and Indian boarding schools were taught to read Dick and Jane and other texts which we now know are detrimental to developing reading skills and information retainment. Today, many school districts in the U.S. use reading lists and curriculum from the 1970s and even states like California still utilize curriculum from the 1990s or the No Child Left Behind era.

During my school years (93-07), I was considered “advanced” and “gifted” because I could read and coherently respond to questions about a standardized list of books classified by age range and “difficulty.” That list hadn’t changed from when my older cousin attended the same school more than a decade prior and neither had the “comprehension” tests, but he was sent to Special Education and labelled “slow” and “learning disabled” due to undiagnosed dyslexia.

Teachers made him read simple chapter books and practice handwriting, he fell behind other kids his age, and he barely graduated high school due to recurring behavioral-related suspensions. My ADHD, Autism, and dyslexia went undiagnosed for decades and I struggled in school, yet I always ended up in Gifted programs or Honors classes because I tested well and teachers said I was a “good writer.”

I left my first high school for an alternative with concurrent college enrollment because I wanted to drop out due to bullying. My cousin still struggles with substance abuse and hasn’t held regular employment. I am riddled with health problems, mental illness, and teach at a university.

“When kids struggle to learn how to read, it can lead to a downward spiral in which behavior, vocabulary, knowledge and other cognitive skills are eventually affected… [and a] disproportionate number of poor readers become high school dropouts and end up in the criminal justice system.”

–Emily Hanford, “At a Loss for Words” (2019)

So what happened? Did I overcome my obstacles because I have pretty cursive writing while my cousin struggles because he “writes like a boy?” Is my relative success due to my childhood love of esoteric literature since he only liked Hardy Boys? But I read The Saddle Club and Batman comics, too. Was that the ADHD trying to sabotage my potential?

We cannot build inclusive classroom spaces that support diverse bodies of students if we start with biased foundations. What works for one person might not work for another and the belief that one form of communication could be superior is chauvinism.

Final Thoughts

Through the 2010s, pop news sites like BuzzFeed offered “quizzes” that asked questions about handwriting to analyze a person’s temperament, romantic prospects, and more. The average person does not know the eugenics origins and applications of these fun quizzes, so the belief that handwriting is somehow an indicator of personality or behavior persists.

Do you want tax dollars teaching kids how to write fancy or do you want them to be able to read an email without handing over their banking information?

There is a reason fascists prioritize taking control of educational institutions and lobbyists during regime changes or in response to resistance–uneducated masses are more easily controlled than a literate polity. To address the illiteracy crisis in the United States, we first need to agree that literacy is necessary for a functional populace, and segregation or stratification by any means is antithetical to a free, progressive state.

Current literacy research fails in two arenas: holistic learning and student autonomy. Neoliberal education is preoccupied with developing standards against which students can be judged through asserting correlation and causation. If research considers factors like reading or writing speed relevant to a person’s intellectual potential, then do we return to eugenics frameworks to account for variation and diversity?

The answer is: fuck no.